Berbers and Omelettes or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love to Hike - The Atlas Mountain Race 2020

Just relax Rob, it’s fine, you’ve done this a hundred times before, find your pace, settle in and turn the pedals, simple right?

This is the script I keep telling myself over and over on day one of the Atlas Mountain Race. It’s mid-morning and a group of two hundred cyclists like myself are speeding south down the highway each with the same task in mind.

As the heat of the day starts to ramp up I find myself puffing for breathe - my mind is racing setting off surge after surge of adrenaline into my system. I say it again.

Relax, deep breathes, control your heart rate and take it easy, this is your race, nobody else’s.

It’s a familiar feeling; the excitement of the start, the giddiness of the open road. Too many times I’ve overcooked it in the first few hours of a race only to pay for it later, I’m not going to make that mistake this time. I finally get my breathing under control.

Bikepacking ultras are a unique type of race set across countries over days with a clock that never stops. The first response when explaining this to the uninitiated is often why? It’s a good question and one I find myself asking repeatedly over the coming week.

Thirty hours have elapsed since the start; the biggest climb of the race is behind me and the longest hike-a-bike I’ve ever had to do. Day two has been good and I’m flying across a desert landscape of broken riverbeds. Imassine is a cool 30km away and I can already taste the tagine - succulent and hearty; the reward for a good day in the saddle and the fuel to keep pushing into the night. No matter how many times I have to carry my bike down into a sunken river bed and climb out the other side, it’s these small thoughts that keep me going - the promise of hot food just a little further down the road.

After hours of an ever rolling landscape of sand and rock, a small set of buildings can be spotted across the plain - this is it! Lifted, I dig in for the last push when thump! In a cloud of dust I’m on the floor - stinging pain and ripped skin - that feeling of being nine years old again picking yourself up, looking for comfort. I assess the damage. The bike is fine with just the bars out of whack, but my palm has lost layers of skin and is bleeding down my fingers. Shit! How could I be so stupid.

I hobble into Imassine desperate for that tagine and to get out the sun. The cafe is off route but happily is full of racers tucking into that famed Moroccan dish. I order one, pull a table into the shade and start to clean myself up. Out of the sun I feel my skin throb - fuck! I’ve done it again - I’ve burnt myself bad. Then comes that voice again.

Why? Why am I out here doing this? What am I trying to prove?

I try to shake the feeling but it doesn’t go, I’m cooked and beat and the idea of moving on is depressing. I take a deep breathe, it’s not the first time I’ve felt like this.

When I tell people at home about these races - how riders aim to cover 200km to 300km in a day - the question is always how? But that’s easy I say. You have all day and the only thing you need to do is eat, sleep and pedal. If you can ride fifty you can ride one hundred, and if you can ride one hundred how hard can two hundred be? Physically you can do it no problem, it’s when you ask yourself why, that’s when the challenge begins.

Luckily this isn’t the first time I’ve asked myself that. When it rained all day and I had to descend for hours in freezing temps in the Alps, or when it took four hours to fix a puncture on a mountain in Bosnia, or that time dogs came out of the dark in the middle of the night to chase. All these times were preparation for this and what did I learn?

This feeling is fleeting

Keep rolling because before long you won’t feel the pain in your hand, or the cold from the wind, soon you will reach the top of that climb, or get that hot food you’d been wanting, or see the sun set in a hundred colours you’d never thought were possible. Because every time you forget why in these races it’s never long until you remember, sometimes it just takes thirty kilometres until you do.

So I push on and I keep going, and with these thoughts I keep ticking off the miles and the struggles start to no longer feel like struggles, instead they just become steps I need to take to get to the next reason to remember why I do it.

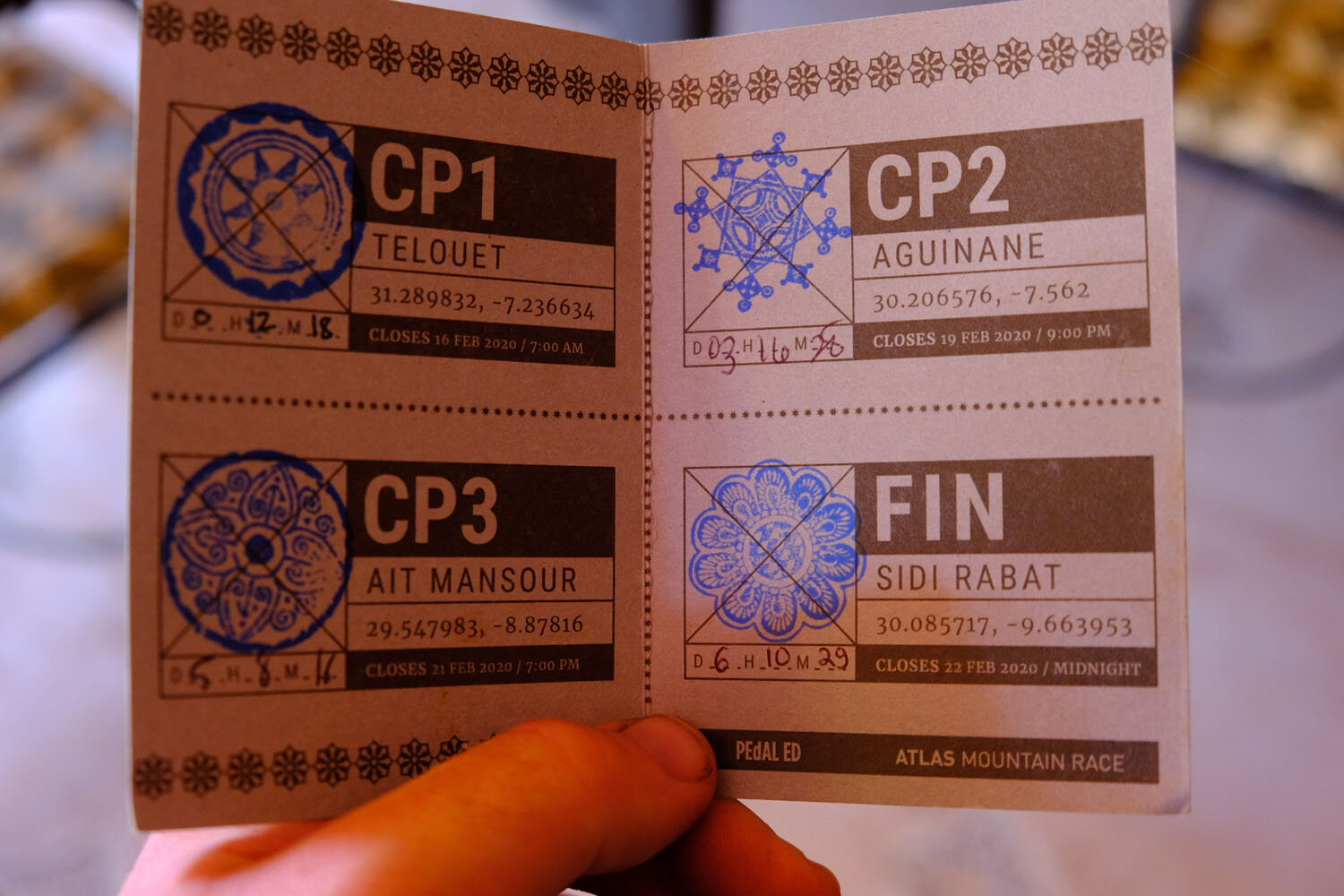

So what has any of this got to do with hiking? Well for anyone who was following the race watching riders trackers they would undoubtedly have seen how after hours of good progress suddenly the dots on the screen would slow for hours or more, barely moving. The reason is hiking!

The remote and wild landscape of the Atlas mountains, zig-zagged with forgotten roads and seldom trodden paths - strewn with rocks and boulders - presented a challenge to even the most accomplished riders. Often the only choice to move forward was to get off and push. For a cyclist this is tantamount to defeat! We ride to conquer these wild landscapes by pedal and to be forced off our bikes can be mentally disastrous. Well that was how I once felt but all this changed for me during this race. While on the road I met a fellow racer who said.

Walking is a tool, it’s another weapon in your arsenal. When you can’t ride get off and push, save your energy, stretch it out, you’ll be the better for it.

It was a revelation! Soon I found myself looking forward to the hike-a-bike sections; they offered a change, some respite and just like that it was no longer defeat, suddenly it was progress! For the first time during a race I saw walking as a benefit.

There are many reasons people sign up to these long-distance races, and for those like me who are mid-pack riders the race isn’t against other racers, it’s a race against yourself. When struggling to navigate inhospitable terrain, or find resupply in the middle of nowhere. When things start to go wrong and you’re picking yourself up after biting dust - these are the crucible moments where your race is made. The battle to go on is often a question of why? And like how I learned to love hiking my bike, the key is finding the joy in it.

For a full overview of the route and a day to day breakdown head to Rob’s Komoot collection.